COVID-19 fatigue: Why do I feel so miserable?

Crisis management experts explain the life cycle of the COVID-19 crisis, your current mood, and what you can do about it.

By Simon Proudlock and Stephen Waddington

Several people in our network have experienced significant issues with mood swings and acute mental health issues in the past two weeks. Anger, anxiety and depression are all common.

Ross Wigham, deputy director, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Trust called it ennui, a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction, arising from a lack of occupation or excitement.

What’s going on?

“Poor decision making, letting things slip and being angry or upset are all symptoms of emotional exhaustion. People have been thinking the worst is over,” said Professor Timothy Coombs, Department of Communication, Texas A&M University.

“Now that light is much further away and that can trigger the emotional exhaustion. It’s hard to imagine you must keep going under rough conditions when you thought things were getting better.”

Coombs developed Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT). He is the author of numerous books on crisis management.

False dawn and societal fractures

We expected the crisis to be over by now, but we’ve now learnt that the easing of lockdown in June was a false dawn. Christmas may be very different than normal.

The new local lockdowns in UK regions and national restrictions have forced people to recognise that COVID-19 will be an issue that we have to live with for at least another 12 months, and almost certainly longer.

It has triggered a change in people's mental health. With little to look forward to, even the most resilient of us are starting to struggle.

Kate Hartley is co-founder of Polpeo, a crisis simulation consultancy. She's also the author of Communicate in a Crisis.

“We’ve all been in a state of fight or flight responding to the pandemic and changes to personal situations such as jobs under threat and financial pressure. That puts significant strain on our bodies and our mental health,” said Kate Hartley.

“Add to that the lack of normal support systems in lockdown such as childcare and the pressure of working from home. Many people are at breaking point.”

Memes such as the new normal, building back better, and the new world, have created the false impression that COVID-19 would be over by now and that we’d be back to normal.

There’s an additional issue that the sense of community that defined our response to the crisis has been fractured by individual responses to the latest phase.

Anti-masks, local lockdown rules and self-isolation are our new value systems. Where we previously supported our neighbours, we’re now being encouraged to report them for flouting lockdown rules.

Lifecycle of the COVID-19 crisis

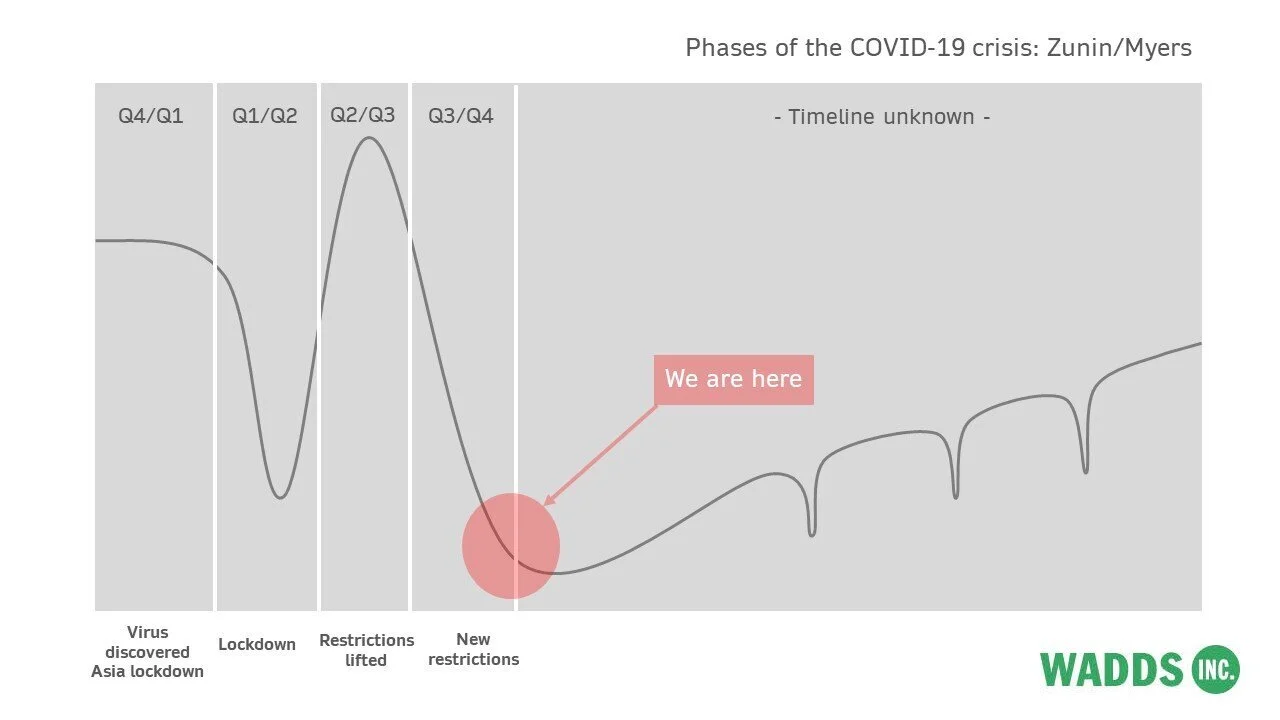

We’ve plotted COVID-19 against a well-known crisis planning model. It provides a clear rationale for our current mood.

The virus was discovered in Q4 2019, Asia locked down in Q1 2020, followed by much of Europe. Restrictions started to lift in Q2/Q3 2020. The cycle has started again with the introduction of new rules (Q4 2020).

Two things are also clear. First, this current situation will pass in a matter of weeks as society continues to innovate and learns to adapt; and second, ultimately, we don’t know how long the crisis will last.

My hunch is that we’re a third of the way through the crisis. We’re learning to live with the virus but need testing, tracing and vaccines in order to fully open up society and the national and global economy.

Living and thriving alongside COVID-19

The constant need to adapt is taking its toll, both in and out of work. We’re becoming burnt out by life itself.

“In a crisis we need time out: to reboot, clear our minds, deal with what’s going on. Most people haven’t been able to do that. We can’t take a break from the pandemic,” said Hartley.

“Without those breaks, we stop being able to function well, or think clearly. Small issues are blown out of proportion. Tempers fray. Our performance dips, and for some people that will increase anxiety about their jobs.”

Sheena Thomson is an issues and crisis specialist who has experienced lockdowns and the restriction of movements in disaster and war environments around the world.

“My only advice – it’s okay to not be okay. Provide a listening service. Often that’s all people need - to have a buddy to share experiences and get their anxieties off their chest. If it becomes seriously disabling, the manager should get occupational health support.”

Amanda Coleman, a crisis management consultant and author of Crisis Communication Strategies makes a related point.

“People have started to neglect themselves due to the way life has become. It is easy to be attached to the computer all the time and be less effective. Why? Because they are not taking breaks, moving away from the work and disconnecting.”

Give yourself a break. It really is okay to have days when you think ‘What’s the point”. Just take one day at a time, and focus on the small things that can make your life a little better.

Go back to all those things you did in lock down to boost your resilience and wellbeing. Be aware of people around you and understand they too might be struggling, worried and burnt out. But mostly keep talking – to family, friends, colleagues. You’re not in this alone.

If you feel your mental health slipping further, reach out to a professional who can help – the sooner you do so the easier your journey back to being you again.

Our professional advice to organisations is to develop a situational plan that is reviewed regularly and evolves alongside the crisis and the changing needs of the organisation, its people, and customers.

Organisations are people. Productivity will inevitably be impacted. Mental health and personal wellbeing must be prioritised.

Let us know if we can help.

Simon Proudlock is a consultant psychologist with Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and in private practice. Simon won the British Psychological Society's Division of Counselling Psychology Annual Award for Innovation in 2018.